The following is a sample mission statement section that can be added into an Investment Policy Statement (IPS). Feel free to pick and choose sections that you may want to adapt; or, use it to inspire your own. A mission statement can be inserted into an IPS for any investor—endowment, foundation, family office, or other institutional or private wealth holder—committed to global human rights, with an explicit lens on Palestinian liberation, decolonial practice, and systematic justice. Many of the screening and databases listed here are linked in the resource section of this toolkit.

Keep in mind that your investment advisor uses this statement as their guiding directive for how to invest your money. In all likelihood, they will be less familiar than you with movement-related goals, so it is best to be as concrete and specific in your language about external guidelines they can use.

I. Investment Philosophy

We believe that investments are never neutral. The structure of capital markets reflects historic and ongoing systems of extraction, settler colonialism, environmental violence, and labor exploitation. As such, we commit to an investment philosophy that aligns our portfolios with our mission and values across all dimensions.

- Movement Alignment: Our investing must reinforce, not undercut, the causes and communities we support. We are accountable to grassroots movements and organizers whose work guides our political, financial, and moral compass.

- Mission Integrity: When investments conflict with mission, they weaken trust, impact, and effectiveness. Alignment is not optional—it is necessary for institutional coherence.

- Profit Is Not Singular: There are many ways to generate returns. Risk-adjusted performance must also account for environmental, social, and ethical realities, including the cost of harm.

- Flexible Return Profiles: Mission-aligned investing can be applied across the full spectrum—market-rate, catalytic, or concessionary investments. The priority is alignment, not one-size-fits-all metrics.

- Investor Power: As asset owners, we possess leverage. We accept the responsibility to apply economic pressure to challenge injustice and support collective liberation.

- Historical Roots: The modern mission-aligned and ESG investing movement was born from calls to divest from apartheid South Africa. As Nelson Mandela said: "We know too well that our freedom is incomplete without the freedom of the Palestinians."

- Intersectionality: The forces that violate Palestinian rights are often the same actors behind carceral expansion, border militarization, labor exploitation, and environmental degradation. We embrace a cross-movement approach that links struggles for freedom and justice everywhere.

- Whole-System Alignment: We commit to embedding human rights, ecological stewardship, and justice values into all areas of institutional operation—including how we made our money, how we invest it, who we hire, what vendors we engage, and how we grant and govern.

II. Fiduciary Responsibility

- Duty of Care: Our fiduciary duty includes not only maximizing financial returns but also avoiding complicity in human rights abuses, climate collapse, and other harms. Fulfilling this duty requires transparency, diligence, and ethical clarity.

- Legal and Moral Risk: Investments tied to state-sanctioned violence, such as those profiting from Israeli apartheid or military occupations, carry reputational, financial, and legal risks.

- Compliance with International Law: Our investment decisions will comply with international human rights law and standards, including the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights.

- Personnel Accountability: This responsibility extends to the Chief Investment Officer, investment committee members, consultants, and fund managers.

III. Responsibility for Implementation

- All fiduciaries, including board members, investment office staff, consultants, and outsourced Chief Investment Officers (OCIOs), are responsible for upholding this mission-aligned investment policy.

IV. Transparency and Reporting

We commit to transparent, ongoing reporting of:

- Portfolio Holdings and Exposures: Including sectors, geographies, and companies identified by human rights and movement-aligned frameworks.

- Investment Changes: Including divestments, re-allocations, and positive tilts.

- Shareholder Engagement Activities, including:

- Proxy voting decisions and justifications

- Shareholder proposals filed or co-filed

- Participation in collective investor campaigns (e.g., coalitions, declarations, industry engagements)

V. Investment Approach and Guidelines

Our investment strategy includes the following practices:

- Cross-Cutting Guidelines: ESG integration, positive screening, and mission alignment will be applied across all asset classes and fund structures.

- Positive Tilts: We will proactively allocate capital to funds, companies, and strategies that are aligned with human rights, climate justice, and community ownership.

- Divestment Criteria: Some industries or companies are fundamentally incompatible with our values. Divestment will be prioritized where engagement is not viable or harm is ongoing. Divestment screens will be implemented based on the recommended divestment lists of the following databases. Screens will be reviewed on an annual basis to ensure that the portfolio’s divestments are in alignment with the latest recommendations of the following organizations:

- (1) BDS Target List;

- (2) American Friends Service Committee Divestment List;

- (3) United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner Database on enterprises operating in illegal settlement activity in the Occupied Palestinian Territories.

- Manager Selection:

- We prioritize asset managers who demonstrate alignment with social justice values.

- Managers must be willing to engage on impact, transparency, and alignment practices.

- Investment staff will engage with managers to deepen alignment, and replace those unwilling to meet values-aligned criteria.

- Managers who engage in activity that endorses violations of human rights—even if not directly linked to their funds—will not manage portfolio capital. This includes firm partners who may make inflammatory comments on public platforms or perpetuate rhetoric that is contradictory to our organization’s mission and values.

- Impact Investing: Where possible, we will deploy capital to community-led, regenerative, and reparative projects offering measurable positive environmental and social outcomes.

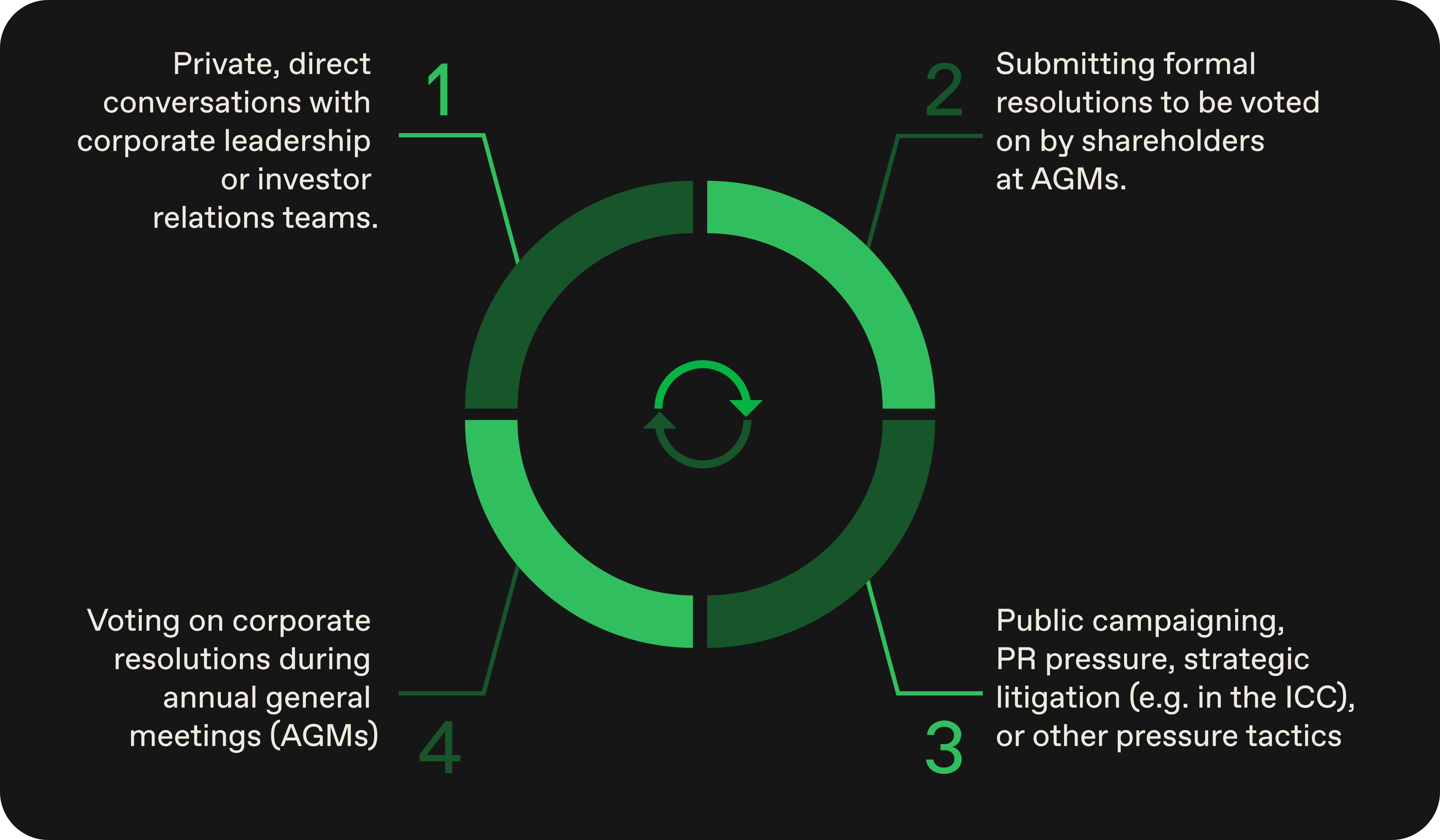

VI. Shareholder Advocacy

We believe in using all available tools for corporate accountability, while acknowledging the limitations of shareholder engagement. Our approach includes:

- Proxy Voting: Informed by human rights frameworks and aligned coalitions.

- Shareholder Resolutions: Filed independently or collaboratively, targeting corporations complicit in rights abuses.

- Direct Dialogue: Engagements must be informed by movement priorities and led where possible by frontline voices.

- Coalition Building: We support and participate in investor networks advancing Palestinian rights, Indigenous sovereignty, racial justice, and environmental justice.

- Investor Organizing: We commit to leveraging investor power to organize for collective pressure and policy shifts.

VII. Data Utilization and Movement-Aligned Datasets

We acknowledge gaps in mainstream investment data and commit to expanding our analysis using:

- Nontraditional, Justice-Rooted Datasets, including:

- AFSC Investigate Project

- BDS movement datasets

- WhoProfits.org

- UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (UNOHCHR) Database

- GenocideVC

- EthicsVC

- Worker and Movement Intelligence:

- NoAzure for Apartheid

- NoTech for Apartheid

- Employee- and worker-led disclosures

.png)

-min.png)

.png)